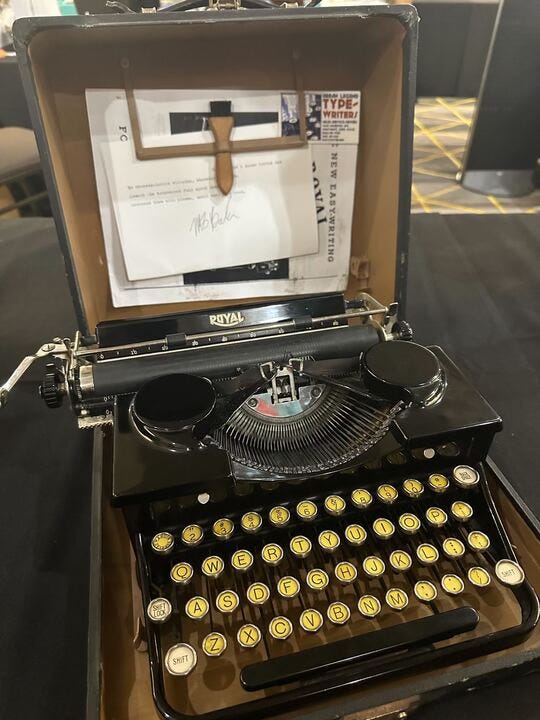

Author Jesse M. Slater is bananas for typewriters. While visiting the Raconteur Press booth at Imaginarium this year, he even brought one with him! We’ll let him explain the madness.

Typewriters? In 2024?

Are you nuts?

Well, yes, probably. The End. Check back next week for more brilliant and amusing stuff from the staff at Raconteur.

What? You're still here? You still want to know about typewriters in the 21st Century? Okay, then, you asked for it.

Yes, I use a typewriter. (Ironically, I'm typing this on a computer, which becomes extremely meta. I'm going to try not to think about that too hard.) I do, in fact try not to be the annoying hipster in the coffee shop, clattering away and annoying the rest of the world. But I also think it makes my writing process better. Getting started, it made writing possible. Let's take a look at why I say that.

I don't know what they teach in writing/composition class these days, but when I was in school, we were taught the rough draft, revise, rewrite (possibly several times), final draft approach. Computers were around, but they hadn't yet become ubiquitous. I hated the "wasted work" of the rewrites. I did my best to avoid them, and convinced myself that if I tried hard enough, I could turn in a clean first draft. (Incidentally, there are actually people who can do this. I just am not one of them.)

What I managed to do, instead, was work my way into a terrible case of cursor paralysis. I'd sit and try to craft perfect words with much sweat and agony and slowness. Because I have ADHD, there was much staring out of windows, fidgeting, and as computers progressed, much Googling and Wikipedia searching in the name of research. What there wasn't much of was actual writing.

I wanted to be a writer for years, but was never able to make headway. I'd start things, and never get anywhere. If I did sweat out a few paragraphs, I'd come back the next day and think it was all hopelessly stupid, and delete it all.

We won't discuss how many years went by like that, but eventually, I stumbled across the idea of the "crappy first draft." Don't try to edit on the fly. Don't try to make it perfect. Turn off the critic, and just write. You can't edit what you haven't written. I tried it, and things were somewhat better. Still, the temptations of the Internet were just a click away.

A while later, I started seeing "distraction-free writing devices," basically a retread of the old "word processors," the intermediate step between typewriters and computers, from the late 80s and early 90s. But what did they want for these beauties? More than a thoroughly decent laptop. I read a few articles, and thought the idea sounded promising, but also ridiculously overpriced. When one of the reviewers called the machines "glorified typewriters," I had a flash. Typewriters were cheap. Thrift stores, Marketplace, Aunt Alice's attic…for a few bucks, or maybe even free ninety-nine, I could have the real thing. And since I'm the type who loves 1911s and revolvers, iron sights, loose tea brewed in a pot and paper books, that was infinitely more appealing.

I went online and found that I was not alone. I started researching typewriters, and found that there's a significant online community who've traveled the same road. Not all are working writers, some are the hipsters referenced above, but a surprising number are finding that typewriters make for better writing.

There's a blogroll called the Typosphere. A surprising number of YouTubers make typewriter content. (TypeTube?) There are books like "The Typewriter Revolution" by Richard Polt, a professor of philosophy at Xavier University, who moonlights as a typewriter repairman, and "The Distraction Free First Draft" by Woz Delgado Flint.

After my usual excessive amount of research, I bought my first typewriter, a 1938 Royal KHM, a big office machine (called a standard) in glorious black enamel, with the classic glass-topped keys. I was off and typing—except I needed to learn to type again. Manual typewriters are extremely technique dependent, and ones this old even more so. A lot of people think that pushing the keys really hard is the answer. Try to drive the type slug through the paper. Really, though, one does strike the keys quickly, but it's helpful to pretend you're touching a hot stove. Quick, light, and get off again.

It took time, as most things do, but eventually, I was typing. Later, I wanted to type on-the-go and got my second machine, a 1932 Royal Model P, also of the glorious glossy black with glass and chrome keys school. That one was an "as found," and took considerable work to get typing.

See, nearly all typewriters are 50, 60, or more years old. This one was 90. Most have been sitting, disused, for 30 or 40 years. They can have issues. At the very least, it will likely need cleaned. Oil tends to gum up over time. Often, they're full of little rubber eraser crumbs, have bits coated with ancient whiteout, or are crusted with nicotine. Possibly all of the above. There could be rust, or there may have been mechanical problems that caused it to be put away, to begin with. It'll almost certainly need a new ribbon.

For someone first buying, the simplest way is to buy from a typewriter shop and get one that's already been reconditioned. Cleaned up, fixed, if need be, new ribbon put in, all that jazz. There are a surprising number of shops around. Some are survivors, old men who survived the end of the typewriter era, and went on fixing the few still in use at this office or that, until the modern resurgence. Some are young hobbyists, taking up the torch. Either way, expect to pay several hundred dollars for a professionally reconditioned model.

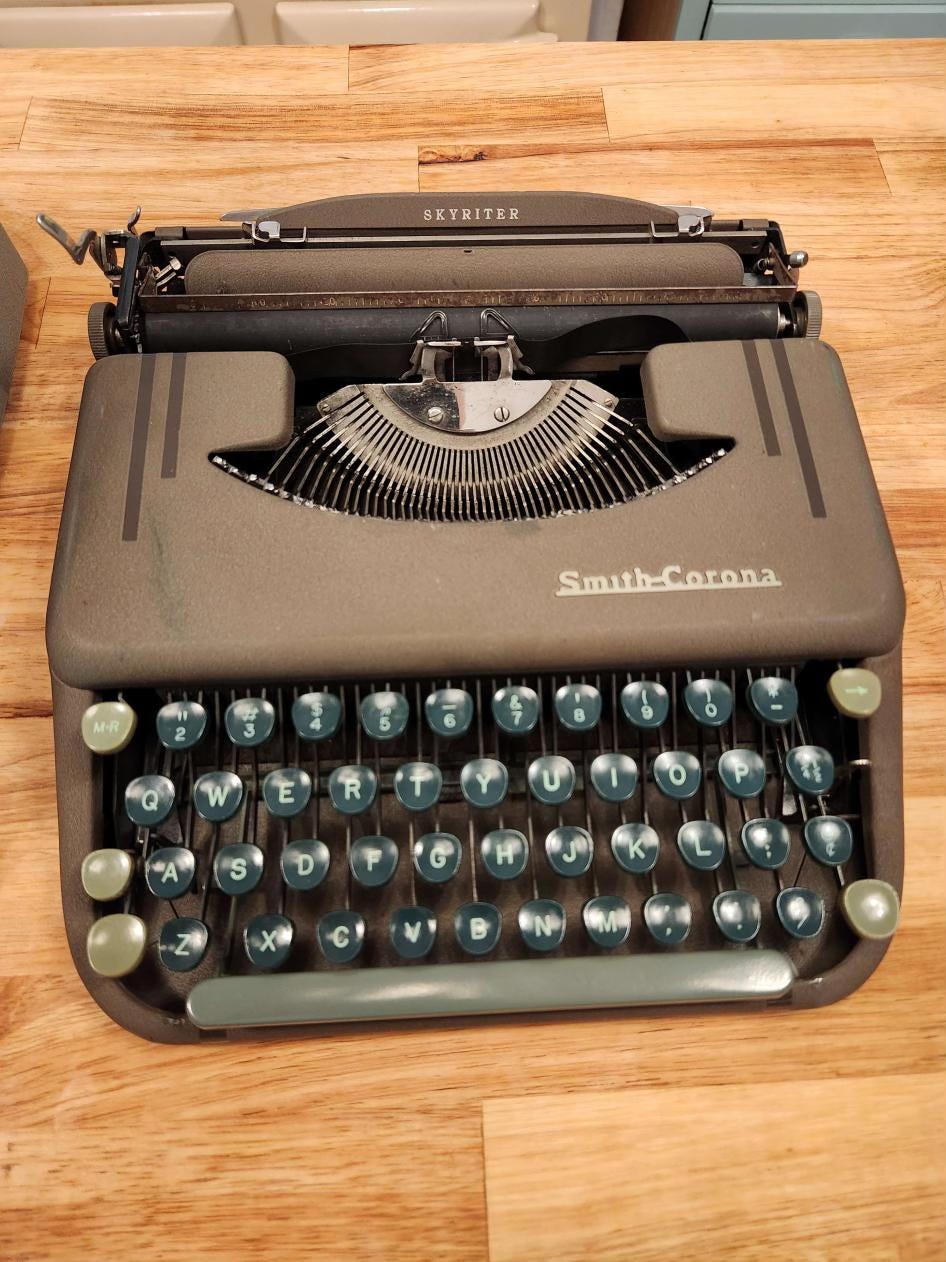

Then there's the approach I've generally taken. Buy one cheap on Marketplace. (Or in one case, find one in the family for free.) There is work involved, cleaning them up, but a little compressed air, some mineral spirits, and a few paintbrushes usually goes a long way. There is also risk. It may have deeper troubles. In the eight I've bought, I've needed professional help with three. But now I have two standard desktop machines, two suitcase-sized "portables," and two briefcase-sized "ultra-portables." (And one that I gave away, one I sold.)

There is also eBay, but the prices tend to be sky-high. Shipping is worse, because typewriters are both heavy and fragile. I'd stay away. Buy locally, if you can.

Speaking of locally, it's often possible to buy ribbons locally. If you're lucky, and the machine you pick takes universal ribbons, Office Max or Staples probably stocks it, though it may be labeled "calculator ribbon." If not, ribbons are all over Amazon, eBay, and the like. There's also ribbonsunlimited.com. They may cost a few dollars more than Amazon, but if you have an exotic machine and need spools for it, or you want something fancier than basic black or black and red nylon (purple and white silk ribbon, or green and gold cotton?), RU is the place.

What else will you need? Typing paper. Regular sixteen-pound copy paper will certainly work, but I find I have better results with slightly heavier stuff. Twenty-four pounds is a good balance. Twenty-eight is very nice, but a little overkill for a rough draft. It's nice for letters, or poems, or other instances where you might want a sturdier feel.

“Okay, Jesse, I've got all this stuff. Now what?” Get to typing. Just tell your story. Don't worry about the typos, or the poor phrasing—just let it flow. Enjoy the tactile feedback of the keys, the machine-gun sound as your fingers fly. Clacka-clacka-clacka DING! That bell is a great little dopamine hit. Don't you want to hear it again? Keep writing. Hear it call you onward. Watch in satisfaction as the pages stack up. Look, look! I wrote a book!

"Jesse, I can't submit this pile of paper to anyone! First, it's terrible, and second, this is 2024!"

Very true. That is where the rewrite comes in. I've got an old-style secretarial document stand, and I set it up and key it in. At the very least, I'm cleaning up all the typos and stuff, but usually I make significant changes as I rewrite, improving the story well beyond what I could do by just editing the Word file. There are some people who skip this step, and scan their typescript using some sort of Optical Character Recognition software, but to me that misses about half the point.

I am honestly glad that I don't live in the typewriter's heyday, as whiteout is an abomination before the Lord. Typewriter erasers are never satisfactory. And retyping a page to catch a typo…ouch. But, with this hybrid process of composing on the typewriter, and rewriting and editing on the computer, I think I have something better than either tool can achieve on its own.

The late Lou Antonelli (ANOTHER GIRL, ANOTHER PLANET) was a newspaperman long before he started writing SF. He wrote on a portable manual typewrite, and then OCR’d it for editing. He’d set his typewriter up at his table in the dealer’s room at conventions, and work on stories during the slack periods.

I’ve often thought the idea setup for an office would be to have a reconditioned IBM Selectric adapted to work as a computer keyboard, so you could simultaneously type a paper copy and create an editable file. If I had that, I’d mark up the edits on the paper copy—your eyes will catch things on paper that they’ll miss on the screen—and then enter them on the computer using a conventional keyboard for that stage.

I learned to type on what I consider to be the best typewriter of all time. The IBM Selectric. Those things were a dream to type on. Smooth. Powerful. klackataklackatahklackatak [DING]

I loved those old things. I cannot use these modern "silent" keyboards some people like to grab. There's just nothing there. Give me a good mechanical keyboard that klackatas at me as I go because that is what I need to keep going. Now if only I could replicate that [DING] I would be in heaven. :)